Series

Season

Subject(s)

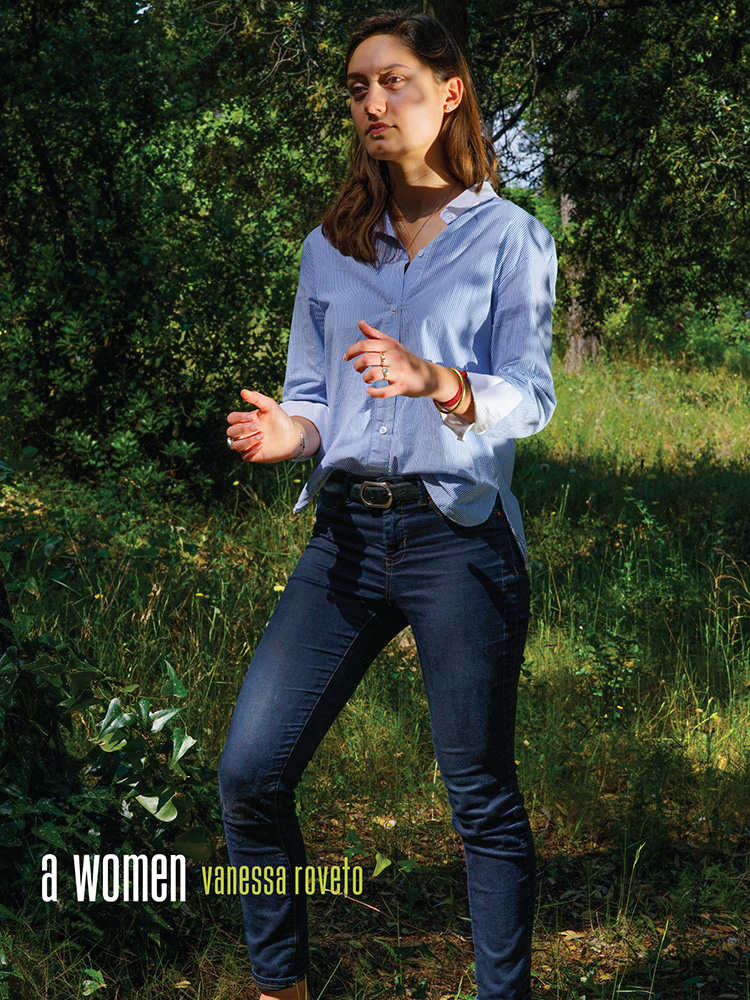

“To survive romantic love, the woman served the other woman desert dirt with shells as the truck stop receded into the distance”—so observes the mordantly detached voice of a women, an extravagantly pained, self-and-other-lacerating imaginative journey dedicated “to relationship.” Auto-ethnographic postmortem on love, fragmented body floating through distillations of desire, sex, and death, lyric fever dream, avant-garde performance piece, manifesto of queer resistance, Vanessa Roveto’s phantasmagorical second book is several contradictory states bound together in a single invented language, resembling but never quite identifying with our own.

“We should all be so aware, so alive, so consequential, so Vanessa Roveto. Language is no match, so she leaves it behind in a rush to explore what it means to her. We’ll call it poetry until she comes up with a better word.’”—Foreword Reviews

“The plurality—or, plural-ness—of Vanessa Roveto’s a women is ingenious and ecstatic, uncontrollable. Ingenious because Roveto is devising a new language within the very limits of American English; ecstatic and uncontrollable because once one starts listening to the extra grammars underneath, within, and alongside words, it’s hard to stop. The plots that unfold within and around these extra- and intra-linguistic spaces are of romantic, filial, and national consequence. To cite Gertrude Stein from The Making of Americans, ‘This is now a description of learning to listen to all repeating that every one always is making of the whole of them.’ Or, as Roveto puts it, ‘resonances discovered in the jumps between posting about it and telling you how I feel.’”—Lucy Ives, author, Loudermilk: Or, The Real Poet; Or, The Origin of the World

“Like those paper fortune tellers folded by young girls, the world(s) of a women are plural, adjacent, playful, shrewd, and constantly unfolding. Roveto makes fluid use of prose form, dressing romance as bildungsroman, elegy as ekphrasis, haibun as virtual reality scroll, each sentence’s gesture seeming to take place in at least two worlds at once. This is writing both replete and exact, brainy and feely, as if the cosmos could be recharted through the most intimate coordinates: ‘her letter became a ladder, an amateur honeypot to the sky.’ I love these succulent, mathy gambits.”—Joyelle McSweeney, author, Toxicon and Arachne