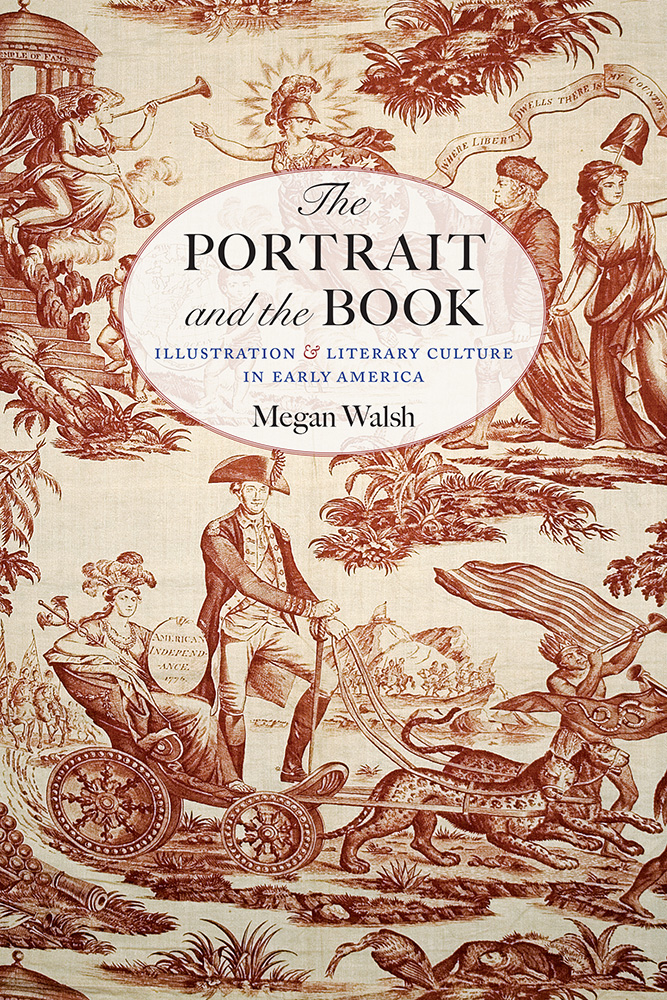

In the nineteenth century, new image-making methods like steel engraving and lithography caused a surge in the publication of illustrated books in the United States. Yet even before the widespread use of these technologies, Americans had already established the illustrated book format as central to the nation’s literary culture. In The Portrait and the Book, Megan Walsh argues that colonial-era author portraits, such as Benjamin Franklin’s and Phillis Wheatley’s frontispieces; political portraits that circulated during the debates over the Constitution, such as those of the Founders by Charles Willson Peale; and portraits of beloved fictional characters in the 1790s, such as those of Samuel Richardson’s heroine Pamela, shaped readers’ conceptions of American literature.

Illustrations played a key role in American literary culture despite the fact there was little demand for books by American writers. Indeed, most of the illustrated books bought, sold, and shared by Americans were either imported British works or reprinted versions of those imported editions. As a result, in addition to embellishing books, illustrations provided readers with crucial information about the country’s status as a former colony.

Through an examination of readers’ portrait-collecting habits, writers’ employment of ekphrasis, printers’ efforts to secure American-made illustrations for periodicals, and engravers’ reproductions of British book illustrations, Walsh uncovers in late eighteenth-century America a dynamic but forgotten visual culture that was inextricably tied to the printing industry and to the early US literary imagination.

“In this elegantly conceived book, Megan Walsh argues that illustration constitutes a crucial paratext in the literature of the early republic, influencing early American writing as much, and sometimes more, by its absence than by its presence. The Portrait and the Book shows how images undergird American literature in surprising and surprisingly early ways, before lithography, daguerreotypes, and photography.”—Patricia Crain, author, Reading Children: Literacy, Property, and the Dilemmas of Childhood in Nineteenth-Century America

“Countering a long-held assumption that the early national period was one of graphic poverty, a low point from which to measure the dramatic rise of illustrated books in the middle decades of the nineteenth century, Walsh taps a diverse archive of verbal and visual materials in order to generate a new perspective on the imaginations of early Americans.”—Eric Slauter, University of Chicago