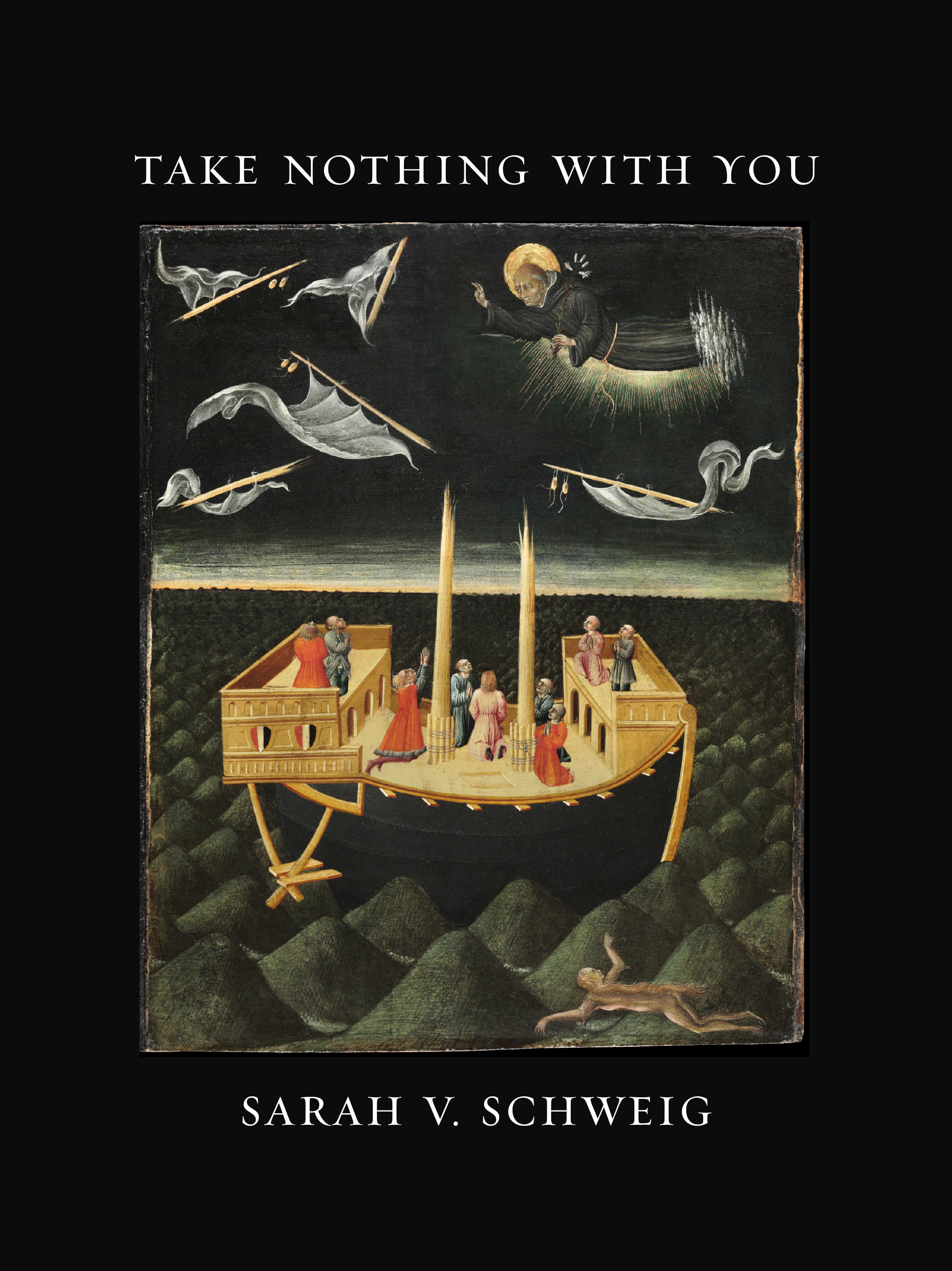

There are worlds we can imagine, but we live in this one: contingent and absurd. In her first full-length collection, Sarah V. Schweig aims to capture something essential and universal about this faulted inheritance.

These poems operate on the notion that the lyric can be discovered in scattered headlines, office-wide emails, road signs—the detritus of the everyday. But a poem doesn’t stop at found fragments; it creates something from them. These poems question and requestion what can be truthfully said, rediscovering the lyric in the very process of thinking, revising, and re-envisioning.

“What we have in Schweig’s poems—full of dark panache and a cool, even murderous, wit—is an auspicious debut.”—Mark Strand

“These poems forge new paths where worlds have disappeared. Out of the tenuous rises the emphatic, with possibilities offered like prayers.”—Ann Beattie

“The effect of reading Sarah Schweig’s verse is quietly dazzling and hard to describe: hallucinatory nuggets of feeling are shaped through extraordinary formal precision, apparently everyday observation, a taste for bathos, repetition, and great precision of utterance. And the whole is full of longing and desire. Tinged with delicious regret and distance, Schweig evokes depth of feeling that will resonate with the reader. No, this is not nothing, but something fine indeed. It is a remarkable achievement.”—Simon Critchley

“These poems issue from a mourning for a ‘missing’ one (father, lover, child, God), an affliction of abandonment that propels the speaker into a triangulated, contingent world: a welter of cities, love affairs, dazzling sonic performances, and philosophical travel—including ‘treatises’ on nada and syllogisms on meaning (‘there is no heaven, and no answers / to our questions’). Witty, intellectually ruthless, the mantra of these poems seems to be: travel lightly in this world of woe. ‘Take nothing with you.’ Yet, however unlikely it may be to believe in, let alone bear the onus of, anything ‘PURE and PERFECT,’ this remarkably mature first book joins the ages-old dialogue about beauty, truth, and love: the (trans)figuration inherent in all ardor, all making. ‘Once there was a man, and then there wasn’t,’ she writes in a tour de force elegy for the late poet Mark Strand. How to respond to such loss except ‘cover my face with my hands?’”—Lisa Russ Spaar

The Abandonment

A man I once loved has built a mountain.

You’re avoiding something, I say when I’ve climbed to its crest.

That’s a projection, he says, repairing the thatched roof on his modest hut.

You’re projecting that I’m projecting, I say, Because your parents were psychoanalysts.

I sit down in the plastic grass, which he’s woven leaf by leaf into the turf.

You’re using description of a moment to avoid what’s really at hand, he says.

But I live for my art, I say. I don’t have anything else.

You had me once, he says, and you still said that.

When I ask if he would like to go swim in the Lake of Remembrance,

he says, Don’t change the subject. When I ask what I can do to help, he says,

Here is a shovel. The mountain never brought him happiness. The mountain never brought him peace. Now we will bury the ash of our teachers. On this we could agree.